"Give us this day our daily bread"

-The "Our Father" prayer

This week, another admission: I despise social documentaries. Jesus is it good to get that pressure off the windsacks. Oh sure, I’ll go see documentaries with my friends and agree that yes the director was almost lyrical in her framing of shots and oh definitely the human subjects developed a very natural and conversational rapport with the camera and these are all lies, LIES. If I have ever gone to see such a documentary with you, and we have talked about it afterwards in generally positive terms, I was lying to you. Through my teeth. I am so sorry.

Here is what I really think: Social documentaries are insufferable, manipulatively edited moral vehicles. They are secular sermons gussied up and masquerading as reporting, bolstered by the weighty claims to real representation that the medium of film offers. Ooooh I hates ‘em.

Now, one last admission: I just saw a remarkable documentary. It is called Unser täglich Brot (Our Daily Bread), from Austrian director Nikolaus Geyrhalter.

Here is what I really think: Social documentaries are insufferable, manipulatively edited moral vehicles. They are secular sermons gussied up and masquerading as reporting, bolstered by the weighty claims to real representation that the medium of film offers. Ooooh I hates ‘em.

Now, one last admission: I just saw a remarkable documentary. It is called Unser täglich Brot (Our Daily Bread), from Austrian director Nikolaus Geyrhalter.

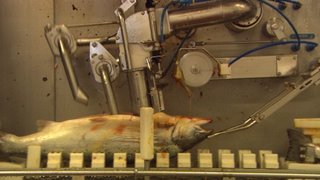

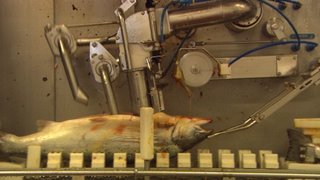

It aims to do nothing more, it claims, than to depict the harvesting, mining, production, and processing of food in the European Union. As my town’s gnarled and dedicated film-swami stood before the theater audience and introduced the movie, praising it for its neutrality and its pretension only to report, I sneered my special sneer reserved for social documentaries and snacked upon my Haribo gummy candy with increasingly hateful intensity. The film started. I took in the long, extended shots of chicken factories, row-crop fields, slaughterhouses, salt mines, and sorting plants, waiting—just waiting—for the director to expose the plight of the immigrant rutabaga-picker or the moral vileness of the charnel house. But such revelations never really came. Sure, the work of the harvesters and factory workers was tedious, and factory farming / slaughtering can be gruesome. But there were no interviews, no exposés, no veneer yanked away to reveal a consciousness-altering reality. Just shots of people carrying out a task and then a few brief glimpses of them on a smoke break.

For like an hour and a half.

The film simply put into belabored detail what most of us already suspected about its subject— picking tomatoes all day is real boring, immigrants do it because Europeans don’t want to, slaughtering pigs is nasty and bloody, and so on and so forth. Oh wait I lied again, the film did reveal a few things—salt mining is far, far radder than any of us could ever have known, and chicken rearing gives rise to a few moments of unintended but inspired hilarity, usually involving confused chickens in various stages of maturity being shot out of cannons and sucked into huge vacuums.

picking tomatoes all day is real boring, immigrants do it because Europeans don’t want to, slaughtering pigs is nasty and bloody, and so on and so forth. Oh wait I lied again, the film did reveal a few things—salt mining is far, far radder than any of us could ever have known, and chicken rearing gives rise to a few moments of unintended but inspired hilarity, usually involving confused chickens in various stages of maturity being shot out of cannons and sucked into huge vacuums.

picking tomatoes all day is real boring, immigrants do it because Europeans don’t want to, slaughtering pigs is nasty and bloody, and so on and so forth. Oh wait I lied again, the film did reveal a few things—salt mining is far, far radder than any of us could ever have known, and chicken rearing gives rise to a few moments of unintended but inspired hilarity, usually involving confused chickens in various stages of maturity being shot out of cannons and sucked into huge vacuums.

picking tomatoes all day is real boring, immigrants do it because Europeans don’t want to, slaughtering pigs is nasty and bloody, and so on and so forth. Oh wait I lied again, the film did reveal a few things—salt mining is far, far radder than any of us could ever have known, and chicken rearing gives rise to a few moments of unintended but inspired hilarity, usually involving confused chickens in various stages of maturity being shot out of cannons and sucked into huge vacuums. I guess if I had to ascribe some motive to Unser täglich Brot, it’d be a Marxist one, the film focusing as it does (and really, really focusing) on the modes of production. But we are nitpicking now. What I want to tell you all, my friends, because I think my friends are the only ones who read this site, is that I have seen the first social documentary that did exactly what its name suggests: document.