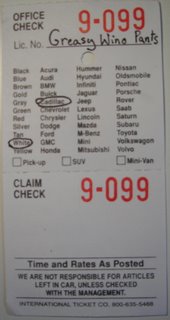

“The most fantastic parking-lot attendant in the world, he can back a car forty miles an hour into a tight squeeze and stop at the wall, jump out, race among fenders, leap into another car, circle it fifty miles an hour in a narrow space, back swiftly into tight spot, hump, snap the car with the emergency so that you see it bounce as he flies out; then clear to the ticket shack, sprinting like a track star, hand a ticket, leap into a newly arrived car before the owner’s half out, leap literally under him as he steps out, start the car with the door flapping, and roar off to the next available spot, arc, pop in, brake, out, run; working like that without pause eight hours a night, evening rush hours and after-theater rush hours, in greasy wino pants with a frayed fur-lined jacket and beat shoes that flap.”

- Jack Kerouac, On The Road

Like Dean Moriarty, the most fantastic parking-lot attendant in the world, this passage may be the most fantastic published work of American Valet literature to date. Moriarty's deft automotive maneuvers dominate his own physical and textual environments; Sal Paradise is hypnotized by this display of spatial genius. Bereft of language that can keep up with Dean, Paradise's description devolves into a pure, primitive mimesis. Struggling to catch his breath, Paradise either carelessly or expertly repeats himself - 'door flapping,' and 'beat shoes that flap' - but perhaps that's just Kerouac's edit-free, benzedrine-fueled style.