“The difficulty of the remainder of this vigorous annal is due, not to ‘the poverty of the English language,’ but to the fact that the writer did not consider the uninformed reader; what he meant was perfectly clear to himself.”

-Alfred J. Wyatt, in a footnote on “The Chronicle” in his Anglo-Saxon Reader

-Alfred J. Wyatt, in a footnote on “The Chronicle” in his Anglo-Saxon Reader

I have a part-time teaching job in provincial Lower Austrian town; I am not a busy man. My great swaths of leisure time are such that I decided I needed a hobby; I have decided that my hobby will be Old English. In Amsterdam a few weekends ago, I picked up a 1925 edition of A. J. Wyatt’s Anglo-Saxon Reader, an old-school chrestomathy of the first rate which, by its own account, contains “any suitable material that had not been drawn upon in earlier works of the same character; … a greater variety of contents than was to be found in some of the books in use,” and finally, “[Nothing] that was not intrinsically interesting”. Mr. Alfred J. Wyatt, you had me at “suitable”.

So after spending a few sweaty, monkish nights poring over Old English verb conjugation and noun declension tables, I opened this book filled with intrinsically interesting things. Its first selection is “The Chronicle”, a bloody narrative of feudal imbroglio in 8th and 9th century England. Before I had read even the first sentence of “The Chronicle” to its end, I was struck by its Style, struck on the head with it over and over again like as if Style were wielding a deadly blunt weapon, and I were its enemy. I give you my own ultra-literal rendering of the confusing, exhilarating first 17 lines:

So after spending a few sweaty, monkish nights poring over Old English verb conjugation and noun declension tables, I opened this book filled with intrinsically interesting things. Its first selection is “The Chronicle”, a bloody narrative of feudal imbroglio in 8th and 9th century England. Before I had read even the first sentence of “The Chronicle” to its end, I was struck by its Style, struck on the head with it over and over again like as if Style were wielding a deadly blunt weapon, and I were its enemy. I give you my own ultra-literal rendering of the confusing, exhilarating first 17 lines:“ 755. Here Cynewulf and the West-Saxon council deprived Sigebryht of his kingdom for wrongful deeds, except for Hampshire, and he had that until he slew that earl who had long lived by him. And then Cynewulf drove him off at the Weald, and there wounded him until a swineherd stabbed him on Privet channel; and he avenged the earl Cumbran. And Cynewulf often fought great fights with the Welsh. And 31 winters after he had had the kingdom, he wanted to drive off a prince who was called Cyneheard; and Cyneheard was the brother of Sigebryht. And then the prince learned of the king being with a small host in the company of women at Merton, and he surrounded him there and attacked the chamber from outside, before the men discovered him who were with the king. And then the king perceived that, and he went to the door, and then bravely defended himself, until he saw the prince, and then he rushed upon him and wounded him greatly; and all were fighting against the king, until they had slain him.”

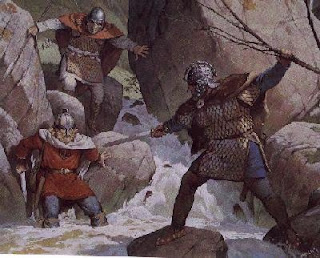

This is one of the earliest prose artifacts in the history of our language. Isn’t it something? Look at that Estilo! It’s like a rhinoceros! Consider how reliant our author was on the word “and” to get a sentence or clause rolling. Homeboy uses it 17 times. (!) “And”, here, is a stylistic device doing the work of more advanced narrative techniques which apparently did not exist at this stage of our language’s prose development. It is indeed sort of poignant and touching to watch little old “and” rise above its lot as simple logical functionary, oft relied-upon but seldom reflected-upon, and wrap itself in the stinky animal skins of Old English prose Style. Instead of bothering with elaboration or causality, the author uses “and” to reassure the reader and perhaps himself that everything he’s saying is related. You can still witness this trick today, when a nervous public speaker is forced to relate a story or argument in front of a crowd. Our composer was also notably fond of “then” (x5) and “until” (x4), which together establish a comfortable but ultimately kind of boring and unfulfilling narrative herky-jerk. Indeed these tendencies towards narrative ease betray a distinctly oral flair; as though English prose in those times was being written by men still cautiously clinging to rhetorical conventions. This is nothing like the practiced gulf separating written and spoken English today, but it was the one of the first teetering steps towards establishing this difference—“The Chronicle”, then, represents English as a cell in the paroxysms of divisive mitosis. No, wait, reader; a metaphor even more wanton: when we read “The Chronicle”, we are watching over the violent birth pangs of our own written Estilo.*

As far as the tale itself is concerned, let the historical record show that King Cynewulf was an

unremitting chump. First off, just speaking generally, the jackass simply could not seal the deal against lesser nobles. He “wounds” his enemy Sigebryht (after which a swineherd—a swineherd!—has to finish Sigebryht off down by the river), and he wounds Cyneheard “greatly” right before getting totally shanked. Let us pause now to consider the circumstances of his shanking. King Cynewulf is in bed thrilling his womens when merchants of death peddling coitus interruptus come calling. He senses their presence, leaps out of bed, girds himself, rushes to the door, lands a (non-fatal) lick on his rival, and then takes a long one in the gut. With his womens behind him, watching and screaming in bed. If I had to think of the worst possible way to go, in all possible universes, I think this is it.

unremitting chump. First off, just speaking generally, the jackass simply could not seal the deal against lesser nobles. He “wounds” his enemy Sigebryht (after which a swineherd—a swineherd!—has to finish Sigebryht off down by the river), and he wounds Cyneheard “greatly” right before getting totally shanked. Let us pause now to consider the circumstances of his shanking. King Cynewulf is in bed thrilling his womens when merchants of death peddling coitus interruptus come calling. He senses their presence, leaps out of bed, girds himself, rushes to the door, lands a (non-fatal) lick on his rival, and then takes a long one in the gut. With his womens behind him, watching and screaming in bed. If I had to think of the worst possible way to go, in all possible universes, I think this is it.Since young adulthood I’ve always had this image of the Anglo-Saxons spending most of their day writhing around lying down in the mud, grimacing and yelling in the mud, having violent, slappy sex in the mud, occasionally taking brief yelly breaks to stab someone they didn’t like. The first 17 lines of “The Chronicle”, insofar as it is a source to be relied upon, have confirmed my youthful suspicions almost to the letter. Without the mud though. But I fully expect to encounter mud in the next few days. I’ll keep you posted.

*One notices this reliance on such joiners as “and” or “for” in many ancient prose literatures; the development of human prose Style is in fact nothing if not the slow, gradual abandonment of conjunctions.

2 comments:

And...?

This is cool!

Post a Comment